The West Texas Waste Wars

by Nate Blakeslee

Texas Observer

March 28, 1997

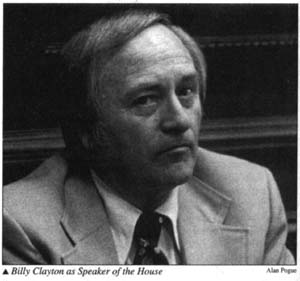

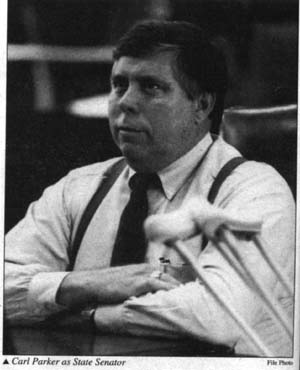

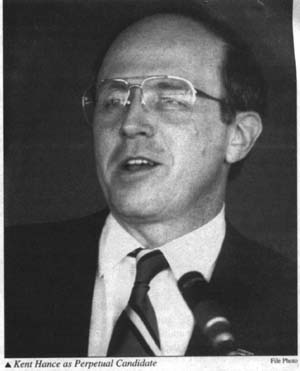

In Austin in the early 1980s, Billy Clayton had just ended his tenure

as Speaker of the House, Ann Richards was the new state treasurer, and Carl

Parker and Chet Brooks were powerful state senators representing Southeast

Texas. In Washington, Congressman Kent Hance represented a district on the

other side of the state. And in Andrews, one of the small West Texas oilfield

towns Hance represented, the bottom had dropped out of the oil business.

The oil bust left Andrews resident Peggy Pryor, like many of her neighbors,

out of work. A dozen years later, Peggy works in Odessa, and a new generation

of Texas lawmakers has replaced the Old Guard, at least in elected office.

But for Peggy and thousands of other West Texans, the Old Guard never really

moved on. Instead, they've all become hired guns in the ongoing political

and corporate Waste War that threatens to bring radioactive waste into the

heart of West Texas.

Kent Hance, Carl Parker, and Chet Brooks are all registered lobbyists

for Waste Control Specialists, the company operating a hazardous and toxic

waste dump in Andrews County, near the New Mexico border. Since 1995, the

company has been trying to expand into the highly lucrative industry of

radioactive waste disposal. Envirocare of Utah, a major player in the fiercely

competitive waste industry, has also purchased land in Andrews County, not

far from Waste Control's huge excavated pits. Envirocare hired ex-Speaker

Billy Clayton as its lobbyist and announced that it, too, intended to operate

a radioactive waste dump in Texas.

And in far West Texas, the state's Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal

Authority (TLLRWDA) continues to pursue its own contested effort to build

a state-operated, "low-level" dump near the tiny town of Sierra

Blanca in Hudspeth County. If the Authority's site is approved, Sierra Blanca

will become the repository for radioactive waste from Texas--and for all

so-called "low-level" radioactive waste from Maine and Vermont,

the two states that have signed a waste compact with Texas. Representing

prospective clients of the Sierra Blanca dump are well-placed Texans; for

example, former Palestine representative Cliff Johnson lobbies for Texas

Utilities, operator of the Comanche Peak nuclear power plant (near Dallas),

and feminist heroine (and former Austin Rep) Sarah Weddington is on the

payroll of Maine Yankee Atomic Power Company.

It Never Goes Away

It Never Goes Away

The closing of several leaking low-level radioactive waste dumps during

the last two decades has the nuclear industry worried. Thirty-nine states,

plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, currently share a single

disposal site in Barnwell, South Carolina. Eleven other states use the Hanford,

Washington site, the only other dump that accepts all types of low-level

waste. For the twelve month period that ended July 1, 1994, thirty-three

states--which together produce 43 percent of the nation's low-level waste--had

no access to dump facilities whatsoever. Unable to operate without producing

low-level waste, yet unwilling to fund safe, site-specific permanent disposal

systems of their own, utility companies may soon find themselves overwhelmed

by their own waste.

The origins of the current waste-dump meltdown lie in the late '70s,

when several states closed nuclear disposal facilities because of environmental

violations. In some cases, waste was found buried outside of trenches; in

others, radiation had leaked into groundwater and contaminated water supplies.

Liquids were dumped illegally, and contaminated equipment was stolen and

sold off-site. By March 1979, the dumps in Illinois, Kentucky, and New York

had been closed. By mid-1979, South Carolina was receiving 90 percent of

the nation's waste.

The industry got a real shock from the Three Mile Island disaster in

Pennsylvania, and South Carolina refused to accept the massive amounts of

waste that would result from decommissioning the damaged reactor. Yet the

Three Mile Island story also highlighted a Waste War paradox: no state government

wanted to bear the political and economic burden of becoming the nation's

nuclear waste dump, yet few states wanted to be completely shut out of the

lucrative waste-disposal industry.

In 1980 a federal law codified a compromise: states were required either

to take direct responsibility for their own waste or to form regional compact

agreements, in which one state voluntarily would serve as the host for the

other signatories' waste. By January 1995, forty-two states had established

nine compacts. But the problem was easier to solve on paper than on the

ground. Throughout the '80s and early '90s, only three locations in the

country handled commercial low-level waste: the Barnwell facility in South

Carolina, plus dumps in Hanford, Washington, and Beatty, Nevada. The leaking

Nevada dump was closed three years ago, when radioactive pollutants were

discovered 357 feet below the desert surface--much deeper than scientists

had thought possible, according to the Los Angeles Times. While eleven

new facilities have been planned, only four states have gotten as far as

selecting sites. And none has begun actual construction. Only two states,

California and Texas, estimate completion before the year 2000.

According to a 1995 U.S. General Accounting Office report, the main obstacle

to the new dumps has been public opposition. In Illinois, public outcry

resulted in review of the selected site by an independent commission, which

eventually recommended scrapping the site and re-starting the entire siting

process. Michigan was expelled from its compact when it concluded that its

own environmental laws precluded locating the dump anywhere in the state.

And after widespread civil disobedience, New York has had to repeat the

entire process at a cost of tens of millions of dollars.

The national dump situation has accordingly raised the stakes in Texas.

Diminished disposal space has forced the industry to spend two decades reducing

its waste flow through compacting, recycling and, where possible, substituting

less radioactive isotopes. Several feasibility studies (summarized in the

1995 GAO report) have demonstrated that there is not even enough waste for

the eleven dumps now planned. In fact, more than two or three national dumps,

according to the report, will drive fees so low that profit margins anticipated

by states (and now private investors) will be threatened. This economic

reality--and growing public resistance to new dumps--has raised the very

real possibility that the next dump permitted will become the nuclear waste

repository for the whole nation, for decades to come.

With authorities in Texas predicting that its facility will be operating

in 1998, the eyes of the nation are on West Texas.

The Texas Waste War

In Texas, the process that promises to make the state the nation's nuclear

repository didn't begin yesterday. In 1983 the Legislature formed TLLRWDA,

and directed the agency to find a suitable site to build and operate the

state's low-level dump. Eight years and thirty million dollars later, Authority

director Rick Jacobi--formerly a safety officer at the trouble-plagued South

Texas Nuclear Project--was still looking. Turned away by public opposition

in county after county, Jacobi was finally ordered by the Legislature to

locate the dump in Hudspeth County, near the Mexican border. Jacobi settled

on the Fashkin Ranch, near the tiny town of Sierra Blanca, in an area the

Authority had earlier rejected on geological grounds. The ranch is less

than twenty miles away from the Rio Grande, in the state's most seismologically

active region. Sierra Blanca, a predominantly low-income, Mexican-American

community, had only recently become the recipient of New York City sewer

sludge. Under a deal brokered by the now-defunct Texas Water Commission,

the town receives 250 tons of partially treated sewage sludge by rail each

week. When Jacobi and company came to town, Sierra Blancans said enough

is enough. "Between the poo-poo choo-choo and the radioactive waste

dump," said life-long Sierra Blanca resident Bill Addington, "the

state is turning us into New England's pay toilet."

Addington organized an opposition coalition, which linked Sierra Blanca

with Marfa, El Paso, and Alpine, and has attracted support from across the

state--including opponents from Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin, and Houston,

cities through which the radioactive waste will be trucked. This coalition

has joined Mexican officials from the border states of Coahuila and Chihuahua

and officials from nearly two dozen Texas cities and counties, to force

a contested hearing of the draft license already issued to the Authority

by the Texas Natural Resources Conservation Commission (TNRCC).

As public opposition to the facility grew, public officials began to

take notice. In a January 1993 letter to then-Governor Ann Richards, Democratic

Representative Pete Gallego of Alpine complained of "a recognizable

pattern by state government in general...of dumping every form of waste

near the Rio Grande and its people." At the time, Governor Richards

had good reason to ignore Gallego's complaint: she had just signed the Texas-Maine-Vermont

compact. If Congress approves the compact--still uncertain--it will bring

Texas an initial $50 million to act as the host state, plus considerable

income from utilities in Maine and Vermont for years to come.

Proponents like Richards and industry lobbyist Sarah Weddington have

claimed that the compact is necessary, because it will prevent every state

in the union from sending its waste to Texas. In reality, the compact does

no such thing. Like most waste compacts formed under the 1980 law, the Texas-Maine-Vermont

compact allows a governor-appointed commission to contract to accept waste

from any source, anytime, without legislative (or voter) approval. Texas

generates nowhere near enough waste on its own to fill a three-million-cubic-foot

dump, and by its own projections TLLRWDA could not survive without Maine

and Vermont's waste. If that waste isn't sufficient, the client list could

be expanded. A 1994 ana-lysis by the Houston Business Journal suggests

that the Authority would open the facility to other states in order to keep

it viable.

Proponents like Richards and industry lobbyist Sarah Weddington have

claimed that the compact is necessary, because it will prevent every state

in the union from sending its waste to Texas. In reality, the compact does

no such thing. Like most waste compacts formed under the 1980 law, the Texas-Maine-Vermont

compact allows a governor-appointed commission to contract to accept waste

from any source, anytime, without legislative (or voter) approval. Texas

generates nowhere near enough waste on its own to fill a three-million-cubic-foot

dump, and by its own projections TLLRWDA could not survive without Maine

and Vermont's waste. If that waste isn't sufficient, the client list could

be expanded. A 1994 ana-lysis by the Houston Business Journal suggests

that the Authority would open the facility to other states in order to keep

it viable.

Governor George Bush, who apparently shares his Democratic predecessor's

enthusiasm for importing nuclear waste, has been promoting the compact since

he took office in 1995, although early on he promised that Texas will not

become the "nation's dumping ground." Shortly after Bush made

that promise, Waste Control Specialists began an effort to bring radioactive

waste to its private facility in Andrews County. During Bush's first legislative

session in 1995, Waste Control founder Ken Bigham attempted to amend the

Texas law that restricted disposal of low-level waste to state-operated

facilities. With Waste Control investor Kent Hance leading a team of lobbyists,

the company persuaded Amarillo Republican Senator Teel Bivins to introduce

the company's bill, which was fast-tracked through the Senate. Bigham and

Hance touted Andrews County's superior geology--and its docile demography,

which provided "unprecedented community support" for the private

waste site.

Andrews' business community and local newspaper initially did roll out

the red carpet for Waste Control in 1991--perhaps because there was no mention

of radioactive waste when the company first came to town. Henry Noel, of

Eunice, New Mexico, the closest town to the facility's location, says many

area residents now feel they were tricked. He has begun organizing Eunice

residents to fight the dump. "Kent Hance assured us that they weren't

in that line of business," said Andrews resident Peggy Pryor.

As Waste Control's lobbyists steered the bill through the closing days

of the session, Pete Gallego recognized the opportunity Waste Control offered

his constituents in Sierra Blanca. Gallego amended the Waste Control bill,

adding language that would have moved the state's dump site to Andrews County.

As the 1995 session was ending, it looked like Bigham's legislative strategy

would land him the whole waste enchilada: a license to enter the industry

and a good shot at becoming the operator of the state's compact facility.

Rick Jacobi, sensing a threat to the Authority's existence, launched a counteroffensive

in the classic tradition of bureaucratic self-preservation. In response

to a governor's office query, Jacobi, whose own agency had previously rejected

sites in Andrews County because of the underlying Ogallala Aquifer, offered

his opinion that Waste Control's site would need "further study"

before it could be approved for low-level radioactive waste. Waste Control

protested and got an apologetic "letter of clarification" from

the Authority, according to the Dallas Morning News.

But Bigham soon found himself under attack from another direction. The

Advocates for Responsible Dumping in Texas (ARDT), the Orwellian-named contingent

of pro-compact lobbyists for Maine and Vermont, began pressuring the Governor

to preserve the compact and the Sierra Blanca site. "Our position,"

explained ARDT spokesperson Eddie Selig, "is that the state needs to

follow through on its policy direction of the past fifteen years."

Selig--who likes to soft-pedal the site controversy by insisting, "Let's

not call it a dump"--argues that there should be no private

dump. Although ARDT claims to favor no particular site, it has become the

de facto lobby for Rick Jacobi's Authority. In administrative hearings,

ARDT representatives have testified in favor of the Sierra Blanca dump,

and the group currently maintains an office there, where it holds "informational

briefings" for local citizens and the media. Supporting ARDT's position

is Vermont Yankee Nuclear's lobbyist Deborah Goodell, who warned that a

private company entering Texas' nuclear waste market would threaten the

compact bill in Congress. A May 1995 Governor's Office Policy Council memo

found in the Authority's files brings the Sierra Blanca site argument into

sharper focus: it asked if the Governor had the "willingness to stand

by while West Texas becomes the nation's dumping ground for waste that no

one else will take, in an area that the TLLRWDA rejected?" (Of course,

the memo neglected to mention that the Authority had originally also rejected

the Sierra Blanca site.)

Near the close of the 1995 session, Bigham received what appeared to

have been a fatal blow to his legislative initiative to build a private

nuclear dump in Andrews County. His own state representative, Pasadena Republican

Robert Talton, came out against the bill. According to the Dallas Morning

News, Talton and Bigham had butted heads years ago when the two were

police officers in Pasadena. Neither has been forthcoming about the details

of the dispute, and Talton insists that his opposition is based on the obvious

"special interest" nature of the legislation. Whatever his motives,

Talton steadfastly refused to play ball with Waste Control, despite heavy

lobbying by Kent Hance and his team. Waste Control's plan unraveled in the

closing days of the session, when Talton and House colleague Ray Allen accused

Hance of offering jobs and campaign contributions in exchange for changing

their positions on the bill. Hance denied everything, but the damage was

done and the bill died. Round one had gone to the Authority.

Near the close of the 1995 session, Bigham received what appeared to

have been a fatal blow to his legislative initiative to build a private

nuclear dump in Andrews County. His own state representative, Pasadena Republican

Robert Talton, came out against the bill. According to the Dallas Morning

News, Talton and Bigham had butted heads years ago when the two were

police officers in Pasadena. Neither has been forthcoming about the details

of the dispute, and Talton insists that his opposition is based on the obvious

"special interest" nature of the legislation. Whatever his motives,

Talton steadfastly refused to play ball with Waste Control, despite heavy

lobbying by Kent Hance and his team. Waste Control's plan unraveled in the

closing days of the session, when Talton and House colleague Ray Allen accused

Hance of offering jobs and campaign contributions in exchange for changing

their positions on the bill. Hance denied everything, but the damage was

done and the bill died. Round one had gone to the Authority.

But Waste Control would not say die. Bolstered by an infusion of capital

from Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons, Bigham returned less than a year

later with a new strategy designed to appease both the Governor and the

Authority: the company would pursue Department of Energy waste rather than

commercially- generated waste. The potential benefits of the new strategy

were huge: Waste Control could tap into the huge waste flow expected to

accompany the decommissioning of U.S. military bases and supporting industry,

and the company would become a federal contractor, theoretically not subject

to state regulation.

The Department of Energy does business with only one private radioactive

waste disposal firm--Envirocare of Utah--but is attempting to expand its

list of licensed private contractors to solve its own burgeoning waste problems.

Envirocare is fully licensed by the state of Utah, and in correspondence

with Texas legislators the federal government has said it will not enter

into any agreement here without the state's blessing. So the final decision

would be the Governor's. And Bush, it seemed, would inevitably say yes to

Bigham's new partner, Harold Simmons--a good friend and financial supporter,

and the CEO of a multinational corporation with $25 million already invested

in the project.

Simmons' political contributions alone may have eroded much of Waste

Control's real opposition. Between 1994 and June of 1996, according to the

Dallas Morning News, Simmons, Bigham and Hance (who is now Waste Control's

board chair and has an option to buy 25 percent of the company) donated

over $170,000 to Governor Bush and Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock. Simmons

had also discussed the issue with the Governor. "I basically told George

that I was involved in the company as a major investor," Simmons told

the Morning News, "and I wanted him to be aware of it in case

the issue ever came up."

Simmons' political contributions alone may have eroded much of Waste

Control's real opposition. Between 1994 and June of 1996, according to the

Dallas Morning News, Simmons, Bigham and Hance (who is now Waste Control's

board chair and has an option to buy 25 percent of the company) donated

over $170,000 to Governor Bush and Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock. Simmons

had also discussed the issue with the Governor. "I basically told George

that I was involved in the company as a major investor," Simmons told

the Morning News, "and I wanted him to be aware of it in case

the issue ever came up."

For its part, Envirocare was not ready to surrender to a potential new

competitor. Before Waste Control even delivered its proposal to the DOE

or the TNRCC, Envirocare Chief Executive Khosrow Semnani bought up 880 acres

of land near the Andrews county site and fired off a letter to the TNRCC

outlining his plan to go into business in Texas as--what else--a federal

contractor for DOE waste. The TNRCC quickly rejected Semnani's "so-called

application," as Waste Control's spokesman Joe Egan called the hastily

assembled Envirocare proposal. But the effect of Semnani's application was

to serve as a pre-emptive strike against Waste Control, by forcing a TNRCC

policy decision before Bigham could fully develop his own plans.

In a terse letter dated October 18 of last year, TNRCC executive director

Dan Pearson explained that the agency did not have the statutory authority

to license a private facility, regardless of where the waste originated.

The implications for Waste Control were obvious. Pearson's letter went even

further, adding that as a matter of policy the agency would be opposed to

"any scenario or arrangement" that involved state oversight of

a private disposal facility. When asked directly how he would respond to

Waste Control's proposed arrangement, Pearson confirmed that the answer

would be the same.

Bigham's Last Stand

Just before the beginning of the 1997 legislative session, the tide again

began to turn, this time in the direction of Waste Control. In late October

of 1996, Utah was rocked by a major bribery/extortion scandal involving

Envirocare and the former Director of the Utah Bureau of Radiation Control.

On December 18, Bigham received tentative permission from the TNRCC to go

ahead with his Department of Energy proposal. In a carefully worded retreat

from his October letter, Dan Pearson acknowledged that a non-state-regulated

DOE site was at least a legal feasibility, noting that if such a proposal

were formally made it would require a policy decision by the TNRCC's three

commissioners--all Bush appointees.

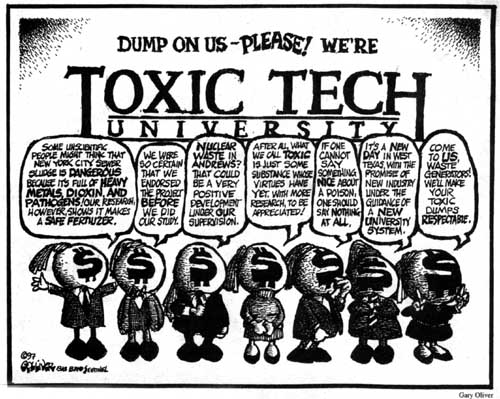

This was all the encouragement Bigham needed. On December 20, Waste Control

submitted its proposal to the DOE, this time with an added twist. Texas

Tech University would become the captain of an "independent private-sector/academe

oversight" group that would first review and approve the company's

application to the DOE and then, under contract to the federal government,

offer continued oversight of the facility's operations. "We're offering

a safe, creative solution to help solve the DOE's disposal problems,"

Bigham's press release read. So creative, it appears, that no one seems

to know if it's legal. The company acknowledged in the text of the proposal

that "there is no direct precedent" for the approach suggested

by the company.

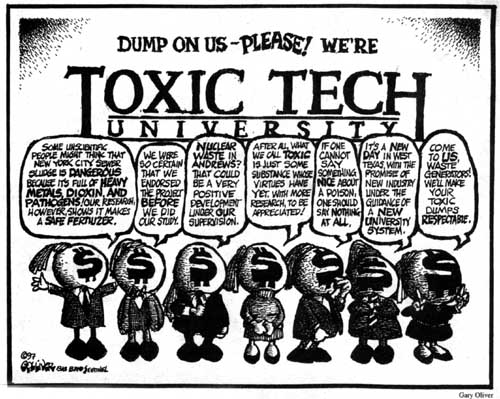

The choice of Texas Tech is perhaps not surprising. The university has

been rented by private interests in the past, so at least there is some

precedent there. West Texans remember that Tech was the sub-contractor that

received a $1.5 million grant to help MERCO Joint Ventures get the Sierra

Blanca sludge operation permitted (with the help of former legislator and

former state water board commissioner Cliff Johnson) in a record twenty-three

days. "These are the folks that brought Texas the largest sewer dump

in the world," said Marfa resident Gary Oliver. And Texas Tech's new

Chancellor, John Montford, was one of the senators who helped Bigham get

his first legislative effort through the Senate in 1995.

In the sewage-sludge permit fight, Tech had some expertise to sell; at

least its rangeland management programs created the illusion of expertise

in dealing with soils and sludge. By its own admission, the university has

no experience with DOE licensure or radioactive waste disposal. "They're

just piggy-backing on Texas Tech," says Representative Talton. Even

TNRCC Chairman Barry McBee acknowledges reservations about the university's

role. "I don't want to discount the abilities of Texas Tech, but there

are existing regulatory agencies in place," McBee said. The chairman

added, however, that the Commission has taken no official position on private

companies disposing of radioactive waste in Texas.

Showdown In Austin

Despite WCS's avowed efforts to steer clear of conflicts with the Authority,

old habits die hard. At a legislative agenda meeting of El Paso city, county,

and state officials held last December, a resolution opposing the Sierra

Blanca site was unanimously approved. According to those present, only one

official wanted to request specifically that the site be moved to Andrews

County: El Paso state representative Pat Haggerty. Ethics Commission filings

show that Haggerty received campaign donations from Ken Bigham, and from

Senators-turned-WCS-lobbyists Chet Brooks and Carl Parker--all on the same

day, and only a few weeks prior to the El Paso meeting.

As late as mid-February, Joe Egan was still discounting the simmering

conflict between Waste Control and the Authority. Egan went so far as to

suggest that a partnership might evolve between the two entities, with Waste

Control processing and treating waste to be disposed in Sierra Blanca. But

at this point, the Authority and its surrogates are not ready to join any

partnership. "Unless I've missed something," ARDT spokesman Eddie

Selig said, any such cooperation would be "news to [me]....Couldn't

another company handle the waste processing for the state?" Selig stopped

short of mentioning that one of the Vermont utility lobbyists, Kraege Polan,

also represents MX Technologies--which according to the governor's office

has already expressed interest in processing the state's waste. Waste Control's

proposal to the DOE contained yet another negative characterization of the

state's Sierra Blanca site, and Chairman McBee is beginning to worry that

"the specter of what might be perceived as competing sides might cause

people to have a [negative] reaction to the compact."

As late as mid-February, Joe Egan was still discounting the simmering

conflict between Waste Control and the Authority. Egan went so far as to

suggest that a partnership might evolve between the two entities, with Waste

Control processing and treating waste to be disposed in Sierra Blanca. But

at this point, the Authority and its surrogates are not ready to join any

partnership. "Unless I've missed something," ARDT spokesman Eddie

Selig said, any such cooperation would be "news to [me]....Couldn't

another company handle the waste processing for the state?" Selig stopped

short of mentioning that one of the Vermont utility lobbyists, Kraege Polan,

also represents MX Technologies--which according to the governor's office

has already expressed interest in processing the state's waste. Waste Control's

proposal to the DOE contained yet another negative characterization of the

state's Sierra Blanca site, and Chairman McBee is beginning to worry that

"the specter of what might be perceived as competing sides might cause

people to have a [negative] reaction to the compact."

On February 27 in Austin, Waste Control laid its cards on the table at

a hearing of the House Appropriations Committee, as Representatives Pat

Haggerty and Talmadge Heflin, supported by Sierra Blanca Representative

Pete Gallego, went after the Authority's funding. According to the few observers

at the early morning meeting, Jacobi never knew what hit him. Peppered by

questions about the agency's bloated budget and questionable past expenditures,

the Authority faced a weary committee grown unanimously impatient with the

issue. "They've expended a tremendous amount of time and resources,"

said committee chair Rob Junell (who also received a $1,000 contribution

from Simmons last year), "and they don't have much to show for it."

Haggerty calculated that the agency had already spent $12 million on legal

fees for only nine days' worth of actual hearings. The committee voted unanimously

to defund the Authority. The Senate might still rescue the Authority's budget,

or at least some of it. But the Authority now seems to be on the ropes.

Envirocare is also under siege. On December 8, Waste Control filed pre-trial

motions in Andrews and began depositions to determine if the company will

sue Envirocare. Those deposed included Khosrow Semnani and Billy Clayton.

As for the Texas-Maine-Vermont compact, its fate in Congress remains

uncertain. Delayed three times by public opposition, the compact bill was

recently reintroduced, this time co-sponsored by twenty-two members of the

House--Republicans Joe Barton and Tom DeLay lead a bi-partisan team that

includes such Texas Democrats as Ken Bentsen, Gene Green, Eddie Bernice

Johnson and Sheila Jackson Lee. According to the El Paso Times, however,

El Paso Congressman Silvestre Reyes has recently come out against the compact.

It remains to be seen whether the fight will turn on environmental principle--or

become simply another shell game over which private interests will be rewarded

the nuclear pie.

Regardless of the short-term political victor, the state of Texas is

not likely to emerge from the waste wars unscathed. Unlike the oil and natural

gas that fueled earlier legislative and regulatory fights, once deposited

in the earth the commodity driving this struggle will never leave West Texas.

Long after the contracts have been awarded and all the hired guns have been

paid, Texans will be living with the legacy of the nuclear industry.

When Ann Richards took office in 1988, she announced the dawn of a New

Texas. But the revolving door from the statehouse to the lobbyist's office

has a way of ensuring that the Old Texas never really leaves us--as Peggy

Pryor, Bill Addington, and thousands of other West Texans understand.

"I'm not convinced that my water won't be contaminated," Pryor

said. "It may be deep, but out here stuff seeps through the ground."

On March 17 she led the town's first non-industry information meeting on

the dump, and she's clearly an excellent candidate for the job. Far better

than the waste profiteers and their hirelings in Austin, Pryor understands

the nature of both the land and the people. And in the end, as she says,

"that's West Texas, you know." Land and people. ¤

Nate Blakeslee is a freelance writer based in Austin. For the past

year, he has been active as a volunteer for the Sierra Blanca Legal Defense

Fund. This article was supported partly by a grant for environmental

coverage from the Wray Foundation. Research assistance was provided by the

Conspiracy of Equals corporate research seminar, conducted at the Info Shop

in Austin.

The Low-Down On "Low-Level" Waste

Low-level waste is generated by the more than 100 utility-owned nuclear

power plants in the country, together with thousands of other industrial

firms, hospitals, universities, and pharmaceutical manufacturers. Low-level

waste is often described by industry spokespersons as consisting primarily

of "gloves, syringes, and booties"--in fact about 70 percent of

the waste by volume is from power plants, which dispose in these dumps everything

but spent fuel rods. A 1993 report by the Washington, D.C. based Nuclear

Information and Resource Service identifies another crucial statistic, seldom

mentioned by industry spokesmen: approximately 90 percent of the total radioactivity

in the nation's low-level waste flow in any given year comes from nuclear

power plants.

The misleading term "low-level" is another topic the industry

is reluctant to discuss. Last month, Texas Low-Level Authority director

Rick Jacobi told the Senate Finance Committee that the hazardous life of

low-level waste varies from "as little as five years" up to "decades"

for some substances.

In fact, as a 1992 analysis by the Institute for Energy and Environmental

Research explains, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission assigns to this category

everything from short-lived radio-isotopes used in research, to extremely

deadly and long lived substances commonly found in reactor waste. Some of

these isotopes--such as plutonium, strontium-99, and cesium-137--remain

hazardous for millions of years.

Near the close of the 1995 session, Bigham received what appeared to

have been a fatal blow to his legislative initiative to build a private

nuclear dump in Andrews County. His own state representative, Pasadena Republican

Robert Talton, came out against the bill. According to the Dallas Morning

News, Talton and Bigham had butted heads years ago when the two were

police officers in Pasadena. Neither has been forthcoming about the details

of the dispute, and Talton insists that his opposition is based on the obvious

"special interest" nature of the legislation. Whatever his motives,

Talton steadfastly refused to play ball with Waste Control, despite heavy

lobbying by Kent Hance and his team. Waste Control's plan unraveled in the

closing days of the session, when Talton and House colleague Ray Allen accused

Hance of offering jobs and campaign contributions in exchange for changing

their positions on the bill. Hance denied everything, but the damage was

done and the bill died. Round one had gone to the Authority.

Near the close of the 1995 session, Bigham received what appeared to

have been a fatal blow to his legislative initiative to build a private

nuclear dump in Andrews County. His own state representative, Pasadena Republican

Robert Talton, came out against the bill. According to the Dallas Morning

News, Talton and Bigham had butted heads years ago when the two were

police officers in Pasadena. Neither has been forthcoming about the details

of the dispute, and Talton insists that his opposition is based on the obvious

"special interest" nature of the legislation. Whatever his motives,

Talton steadfastly refused to play ball with Waste Control, despite heavy

lobbying by Kent Hance and his team. Waste Control's plan unraveled in the

closing days of the session, when Talton and House colleague Ray Allen accused

Hance of offering jobs and campaign contributions in exchange for changing

their positions on the bill. Hance denied everything, but the damage was

done and the bill died. Round one had gone to the Authority. It Never Goes Away

It Never Goes Away  Proponents like Richards and industry lobbyist Sarah Weddington have

claimed that the compact is necessary, because it will prevent every state

in the union from sending its waste to Texas. In reality, the compact does

no such thing. Like most waste compacts formed under the 1980 law, the Texas-Maine-Vermont

compact allows a governor-appointed commission to contract to accept waste

from any source, anytime, without legislative (or voter) approval. Texas

generates nowhere near enough waste on its own to fill a three-million-cubic-foot

dump, and by its own projections TLLRWDA could not survive without Maine

and Vermont's waste. If that waste isn't sufficient, the client list could

be expanded. A 1994 ana-lysis by the Houston Business Journal suggests

that the Authority would open the facility to other states in order to keep

it viable.

Proponents like Richards and industry lobbyist Sarah Weddington have

claimed that the compact is necessary, because it will prevent every state

in the union from sending its waste to Texas. In reality, the compact does

no such thing. Like most waste compacts formed under the 1980 law, the Texas-Maine-Vermont

compact allows a governor-appointed commission to contract to accept waste

from any source, anytime, without legislative (or voter) approval. Texas

generates nowhere near enough waste on its own to fill a three-million-cubic-foot

dump, and by its own projections TLLRWDA could not survive without Maine

and Vermont's waste. If that waste isn't sufficient, the client list could

be expanded. A 1994 ana-lysis by the Houston Business Journal suggests

that the Authority would open the facility to other states in order to keep

it viable.

Simmons' political contributions alone may have eroded much of Waste

Control's real opposition. Between 1994 and June of 1996, according to the

Dallas Morning News, Simmons, Bigham and Hance (who is now Waste Control's

board chair and has an option to buy 25 percent of the company) donated

over $170,000 to Governor Bush and Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock. Simmons

had also discussed the issue with the Governor. "I basically told George

that I was involved in the company as a major investor," Simmons told

the Morning News, "and I wanted him to be aware of it in case

the issue ever came up."

Simmons' political contributions alone may have eroded much of Waste

Control's real opposition. Between 1994 and June of 1996, according to the

Dallas Morning News, Simmons, Bigham and Hance (who is now Waste Control's

board chair and has an option to buy 25 percent of the company) donated

over $170,000 to Governor Bush and Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock. Simmons

had also discussed the issue with the Governor. "I basically told George

that I was involved in the company as a major investor," Simmons told

the Morning News, "and I wanted him to be aware of it in case

the issue ever came up."

As late as mid-February, Joe Egan was still discounting the simmering

conflict between Waste Control and the Authority. Egan went so far as to

suggest that a partnership might evolve between the two entities, with Waste

Control processing and treating waste to be disposed in Sierra Blanca. But

at this point, the Authority and its surrogates are not ready to join any

partnership. "Unless I've missed something," ARDT spokesman Eddie

Selig said, any such cooperation would be "news to [me]....Couldn't

another company handle the waste processing for the state?" Selig stopped

short of mentioning that one of the Vermont utility lobbyists, Kraege Polan,

also represents MX Technologies--which according to the governor's office

has already expressed interest in processing the state's waste. Waste Control's

proposal to the DOE contained yet another negative characterization of the

state's Sierra Blanca site, and Chairman McBee is beginning to worry that

"the specter of what might be perceived as competing sides might cause

people to have a [negative] reaction to the compact."

As late as mid-February, Joe Egan was still discounting the simmering

conflict between Waste Control and the Authority. Egan went so far as to

suggest that a partnership might evolve between the two entities, with Waste

Control processing and treating waste to be disposed in Sierra Blanca. But

at this point, the Authority and its surrogates are not ready to join any

partnership. "Unless I've missed something," ARDT spokesman Eddie

Selig said, any such cooperation would be "news to [me]....Couldn't

another company handle the waste processing for the state?" Selig stopped

short of mentioning that one of the Vermont utility lobbyists, Kraege Polan,

also represents MX Technologies--which according to the governor's office

has already expressed interest in processing the state's waste. Waste Control's

proposal to the DOE contained yet another negative characterization of the

state's Sierra Blanca site, and Chairman McBee is beginning to worry that

"the specter of what might be perceived as competing sides might cause

people to have a [negative] reaction to the compact."